In 1956 in an interview with Selden Rodman, Mark Rothko denies being an ‘abstractionist’ when asked about the use of colour harmonies and the lack of discernible form in his paintings with the retort: “I am not interested in colour or form or anything else. I’m interested in only expressing basic human emotions. The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them and if you are moved only by their colour relationships, then you miss the point!” Rothoko’s deliberate negligence of the elements that pre-modern painters dealt with allows the trained eye access to a relatively latent expression of personal experience. This exclusion would please New York critic Clement Greenberg and conform with his ideals for true art, as propounded in his landmark essay Avant-Garde and Kitsch.

In 1939, against the backdrop of the prevailing art style, American Regionalism, and the societal modifications of European Fascism, Greenberg attempts to distinguish between popular art or Kitsch, born out of mass media and consumerism and the coterminous appropriation of art by totalitarian regimes, from what he referred to as Avant-Garde or genuinely revolutionary art. He opines the former is a spectacle for the masses, marked by mesmerising entertainment, psychic manipulation and illusion. It inevitably gets caught in a vicious cycle of stagnant and academic Alexandrianism whereas the latter stays relevant by using self-criticality and medium specificity in an effort to be autonomous and thereby creates new meaning and originality in a culturally ambiguous society.

Greenberg’s primary concern is visual, he focuses on aesthetics and how it defines art. He illustrates this by examining the experiences of a specific individual and the social and historical contexts in which that experience takes place. The essay is divided into three parts, examining the need for and birth of avant-garde, the rise of kitsch, and concludes considering their co-existence (or lack of it) in the varied societal constructs of Germany, Russia, Italy and the West.

‘The Birth of Venus’, Alexander Cabanel, 1863

‘Starry Night’, Vincent Van Gogh, 1889

Greenberg argues that pre-modern painting and its re-hashed kitsch use tools such as 2 and 3 point perspective to create a representation or illusion, when one is really confronted with just paint and canvas. The viewer encounters Alexandre Cabanal’s Birth of Venus or Van Gogh’s Starry Night and is taken through the ‘window’ that is the canvas, into a theatrical mimesis of reality. Here art is concerned with the worldly matters of culture, politics and religion. Greenberg feels this art is merely regressive trickery as creativity and virtuosity are sidelined to detail rather than encompassing the macrocosm of art. Dissatisfied, avant-garde artists get rid of these relics of european art, away from the subject matter of experience and instead focus on the disciplines and process of art itself, in effect imitating God by creating something valid solely on its own terms, the way a landscape – not it’s picture, is aesthetically valid. This is the genesis of the “abstract”, one that turns from an Aristotelean imitation to an ‘imitation of imitating’. Artists work ‘with’ their materials rather than ‘against’ them; Picasso, Braque, Mondrian, Miro, Kandinsky, Brancusi, even Klee, Matisse and Cezanne derive their chief inspiration from the medium they work in…to the exclusion of whatever is not necessarily implicated in these factors. Photography becomes representational unless it deals with issues of light as video becomes kitsch unless it deals with the inherent narcissism of artist and subject, who are often one and the same. Painting becomes flat yet engages space and tangibility, as process becomes ‘de-skilled’ and spontaneous, albeit most thought occurs prior to the action of painting. This is vocalised by Jackson Pollock, who when asked about Nature in his paintings, succinctly replied : ‘I am Nature!’

‘Autumn Rhythm’, Jackson Pollock, 1950

During this era a burst of technological innovations such as the printing press immersed the world into increased connectedness and opened up avenues of exploration and cross-cultural dissemination of information, which came to be known as popular culture. Popular, commercial art and literature with their ads, slick and pulp fiction, comics, Tin Pan Alley music, top dancing and Hollywood movies gave the working man access to new artistic and stylistic movements and their aesthetic, in the comfort of their homes, without having to own it. It served the function of entertainment in leisure time, a thirst for diversion only culture could provide, thus being a medium of industrialised society itself. Greenberg is less concerned though, with popular culture, than what he would term academic art which guised as avant garde but was in-fact a reappropriated simulacrum. All Kitsch is academic, and conversely, all that is academic is Kitsch, he states. Kitsch draws its reservoirs from accumulated experience, using the devices, tricks, stratagems, rules of thumb, themes and ideas of hitherto high art, converts them into a system, and discards the rest. This powerful tool was mobilised on one hand: Hitler and Mussolini were able to win their political elections due to year-long carefully orchestrated propagandas, flattering the masses by bringing all culture down to their level. In this extreme, the avant garde resorted to flee to the democratic west or face an inner exile of non-confrontational art.

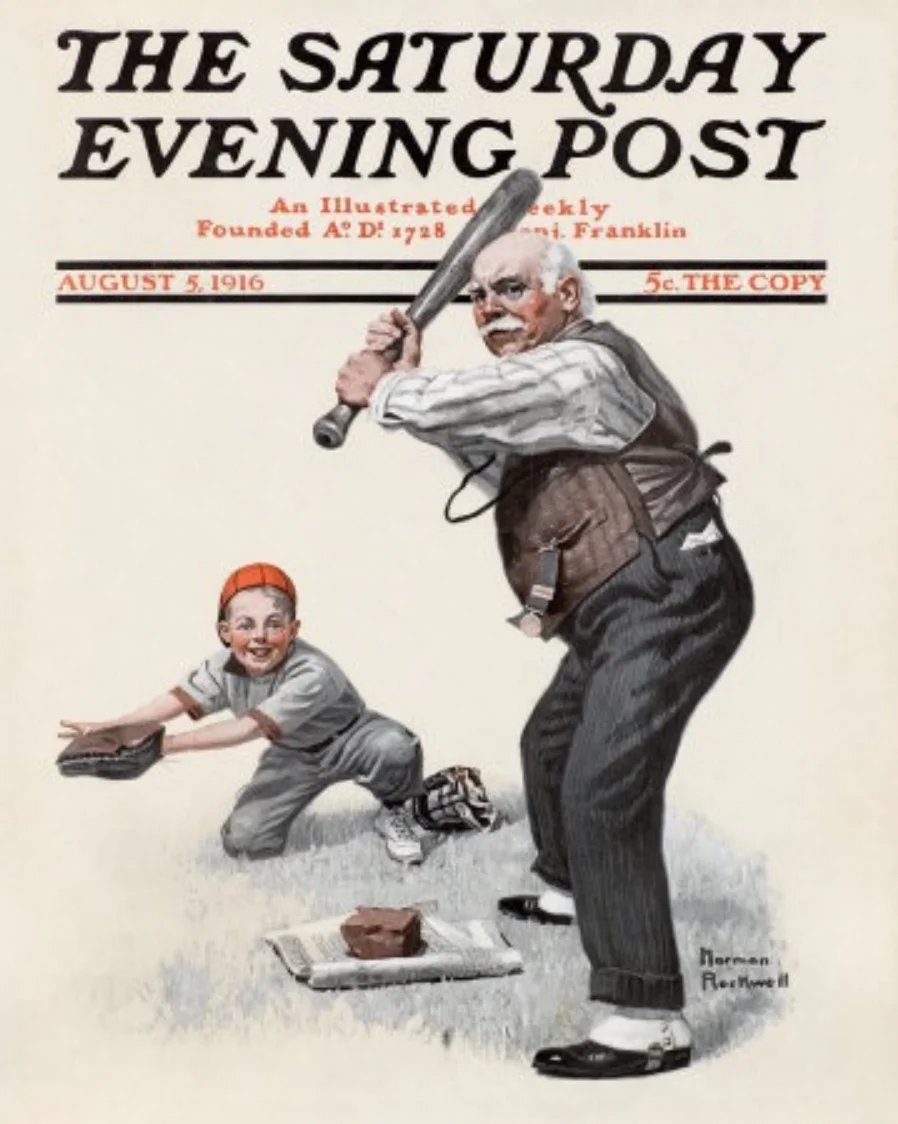

On the other hand, Greenberg despaired the proletariat in the West, that believed it was receiving ‘Art’ every week with the Norman Rockwell covers of Saturday Evening Post. He argues that it is a platitude that art becomes caviar to the general when the reality it imitates no longer corresponds even roughly to the reality recognised by the general i:e; what the latter believe superstitiously, the former believe soberly. The underlying difference between avant garde and kitsch is that the avant garde illustrates the unconscious while kitsch illustrates the conscious, thereby leaving room for the viewer’s personal interpretation. Kitsch is, according to Greenberg, conservative and uncultured, tied to mass production, losing its empathy and humanity.

‘Boy with Baby Carriage’, Norman Rockwell, 1916

‘Gramps at the Plate’, Norman Rockwell, 1916

Notwithstanding the epochal leap towards modernism spurred on by the avant-garde, it’s self-specialisation estranged its exponents, causing bottlenecks in artistic progress. Using a Marxist lens, Greenberg illustrates the irony that the ‘neo–bohemians’ depend on the precarious and shrinking elitist patronage they attempt to escape from: Already sensing the danger, artists become more and more timid every day that passes. Academism and commercialism appear in the strangest places, as the avant grade becomes unsure of the audience it depends on – the rich and the cultivated. The reader is harked back in time, contemplating whether high art over varied epochs compromised itself citing financial impediments and subsequently investigates the magnitude of distortion reflected in their oeuvres, at an individual and communal level.

‘Attic’, William de Kooning, 1949

'Excavation’, William de Kooning, 1950

Greenberg later recognises avant-garde is simply the latest in an evolution of ideals. He portents this new culture contains within itself some of the very Alexandrianism it seeks to overcome. For example, abstract expressionism approaches it’s limits when the artist’s autograph style, albeit unique, ossifies into an academic repetition. One questions the quantitative effort invested by artists when styles become easily reproducible by others, as Pollock incites Willem Dekooning for being ‘the only one who’s made more DeKooning’s’ than he has. Greenberg claims this limit lies in the structural rhetoric of abstract expressionism rather than of the painter. A contiguous regression occurs in minimalism, which displays a heightened sensitivity to spatial context, and in doing so gets caught up in its 3 dimensionality, blurring the line between painting and sculpture.

To conclude, one would like to question Greenberg’s need to elicit distinction between high and low art in the first place. The existence of the two is not new. Since the origins of art, what he terms as kitsch and avant garde have co-existed whether or not explicitly defined, ipso facto artistic evolution; one ‘exists’ so the other can ‘move forward’. In fact, one cannot exist without the other as they are cross referential yardsticks that help define what one is, through what the other is not. It is ironic then that the ‘blur’ between them is due to the limitations inherent in the process of bracketing an individual artwork or artist into one of the two categories. Thus what Greenberg essentially does in this essay, Avant Garde and Kitsch, is map their concomitant rise in the industrial era, and document the form each takes. We see art manifest in a modern ‘ying-yang’ configuration. And it is a credit to Greenberg to have done so!